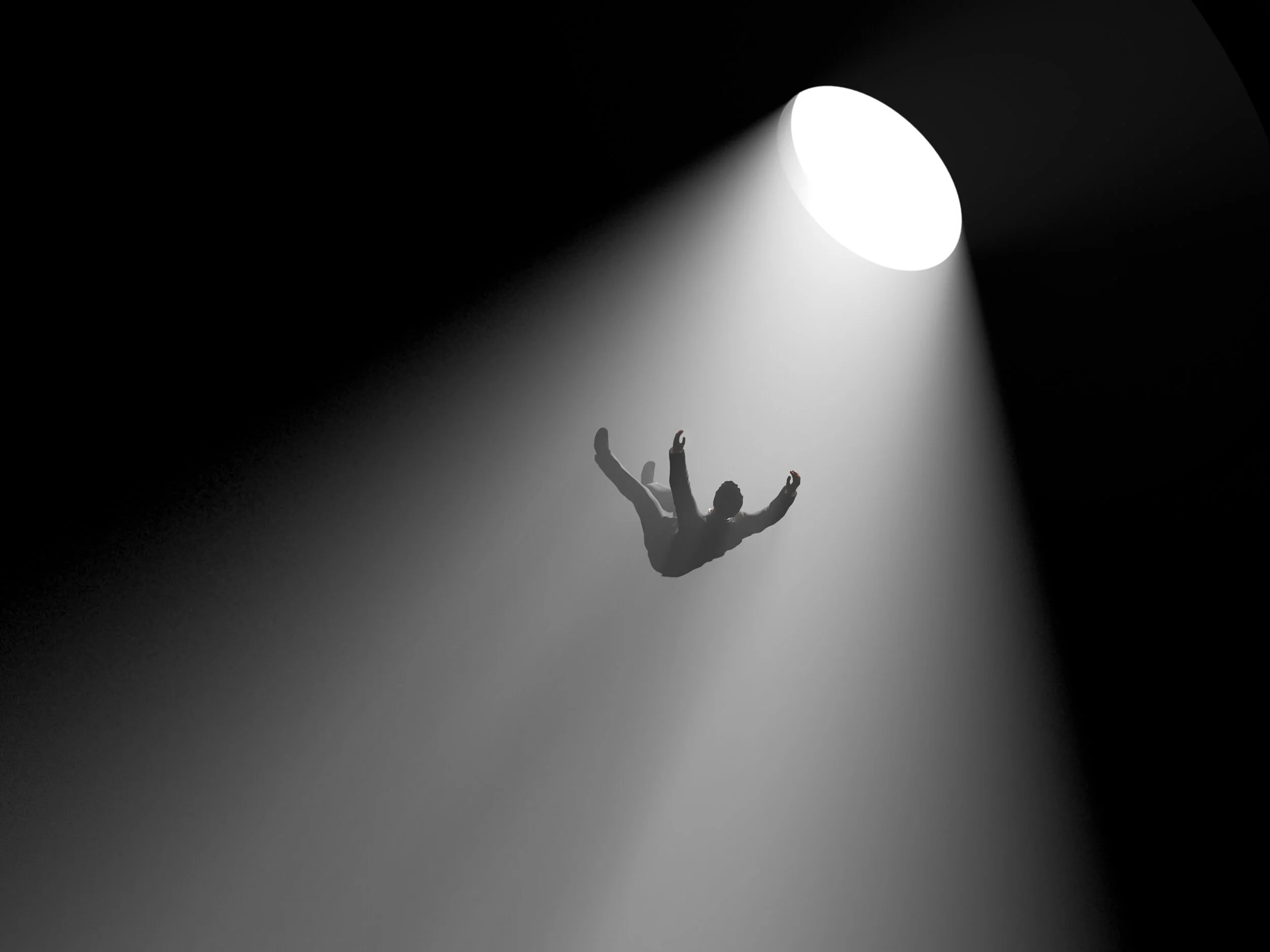

Mental health and depression have always been issues in the chronic and autoimmune community. Every aspect of a physical illness that doesn’t go away can chip away at a person’s well-being. But it’s treatable, and can be mitigated with a good therapist and a regimen that includes a realistic approach to the condition and self-care. But sometimes it just gets to you and you find yourself staring into the abyss of despair. It’s not a technical or medical definition, but to me, despair is the evil stepchild of depression – an exponent or two darker and harder to treat.

One of my friends is dealing with this right now. Though she dealt with cancer years ago, she has been cancer free for over a decade and has since dedicated herself to patient advocacy. But even with all that, she was not prepared for the excruciating muscle spasm that gripped her a couple of months ago and hasn’t let go. Initial attempts at treatment have only made it worse. For the first time in her life, she is suddenly faced with the prospect of a permanent loss of mobility and the ability to achieve the life she wants. She feels like her body is broken, and she is demoralized. The truth is, her body is broken, at least for now. It may never be completely repaired, but that doesn’t mean its unusable. But it’s still scary.

Admittedly, I have never, and will never, be faced with a sudden change like that. The unlimited mobility of youth was mine only briefly. But a lot of us have come to some version of this painful realization through chronic pain or amputations or conditions that require limited movement. The prospect of limited movement has an outsized impact on people because suddenly their independence is threatened. We all want to do for ourselves. It is a fundamental and biological need. Physical limitation is not easily hidden, and any sign of weakness makes us vulnerable to attack. Or just vulnerable. To what people think of us and what we think of ourselves.

My friend has lived an amazing, bohemian life on her own terms. Right now, all she knows is that her body is in enough pain that she can’t sleep or work very well, and there won’t be any answers until she sees her doctor in a week. That’s a long time stuck in limbo (yes, there are folks out there whose diagnoses take years, but that is another discussion). And even then, there are no guarantees of a concrete resolution. Add to that the isolation of the pandemic, and you have all the ingredients of a downward spiral.

I am an expert on downward spirals. I pull myself out of little ones at least a couple of times a year and I have pulled myself out of big ones at least twice. I can’t allow my friend to get sucked in if I can help it.

Which is fine for me. My perspective is different. For years I have lived by the life view that it can always be worse unless I’m dead, and since I’m not dead, I must be doing ok.

But it’s much harder when you’re in it. All you can think of is that this could be the end of the world as she knows it, to borrow a phrase.*

So, I will check in on her daily and remind her that her appointment is only a few days away. I will try to make her laugh. I will tell her that, while prognosis statistics are good for setting expectations, as someone who has blown them up at every opportunity, they don’t actually mean much. And when she does finally get some answers, she can demand that the doctors tell her what she can do, in green, yellow, and red zones. And then she can decide how far to push herself into the yellow. It’s going to be annoying as hell.

That’s fine. She can hate me for a while. I’m good with that. As long as it keeps her from delving too deeply into that downward spiral.

*R.E.M. It’s the End of the World As We Know It (And I Feel Fine), 1991 (which is the year I was diagnosed with diabetes, ironically)