I am one of those people who puts all their eggs in one basket. The more important the issue or opportunity, the more laser focused I become on the one path I want to take. I get all spun up and excited, whether it is likely to work out or not. Sadly, most situations seem to end up the latter. Like the latest one.

For Type 1 diabetics, there are a lot of elements to control. There are also a lot of options to choose from: long-acting and short-acting insulin, separate or mixed; blood sugar monitoring devices, either by finger (or other body part) prick or continuous glucose monitor (CGM); and insulin delivery systems, vial and syringe, pump, or even an inhaler.

I have never been one to pursue the latest gadget as soon as it comes out. I don't like to be the guinea pig, and if others are willing to weather the glitches before I have to, more power to them. It took a long time for my doctor to convince me to get a pump, but that was the only major change I made from the basics chosen for me at diagnosis. I tried a few CGMs, but they never worked, and I was happy with the regular finger prick method. Until recently, that is.

My recent detour from my regimen has resulted in progressively worse control, and I was starting to feel desperate, mostly because I no longer understood how my body worked. None of the biorhythms I had learned over the decades applied anymore. When one of my providers suggested a six-month-old technology that would intuitively keep my blood sugars in a good range, I dumped about two dozen eggs into that basket. It would be easier and quicker than any other option.

Once I made the decision to go forward with the combination pump and CGM, I wanted it now, which turned me into a bit of a Ms. Hyde. I am not entirely proud of how I handled some of the communications involved, but everyone came through for me (shout-out to Blue Cross Blue Shield CareFirst Administrators, who approved my new device in less than 24 hours even though I had six months on my old pump warranty. Never thought I would say that.).

I spent a few hours getting trained on my new device, setting it up and navigating it, putting all the pieces together and putting them in the right places on my body. And then, and then . . .

Not once did it occur to me that it wouldn't work.

Even though not one of the previous attempts to use a CGM had worked, I just couldn't accept that it wasn't working. I tried for over a month, tweaking the tech, moving the glucose sensor, but the CGM just wouldn't read accurately, and even when it did, the pump couldn't keep up with its readings, so my blood sugars remained high.

Well, what now?

Cheat, that's what, at least as much as I needed to. If that word is uncomfortable, think of it more as making my own rules, something at which I excel.

I moved the glucose sensor to an area on my body not approved by the FDA and turned off the artificial intelligence (AI) part of the tech, which was supposed automatically adjust my base rate insulin. Suddenly the readings, while still high, were looking a lot more accurate, so I let it run another week to make sure it wasn't just one accurate sensor. (It wasn't. ) Well, that was exciting. But when I tried to turn on the AI again, the whole thing malfunctioned, including the sensor. Not so exciting.

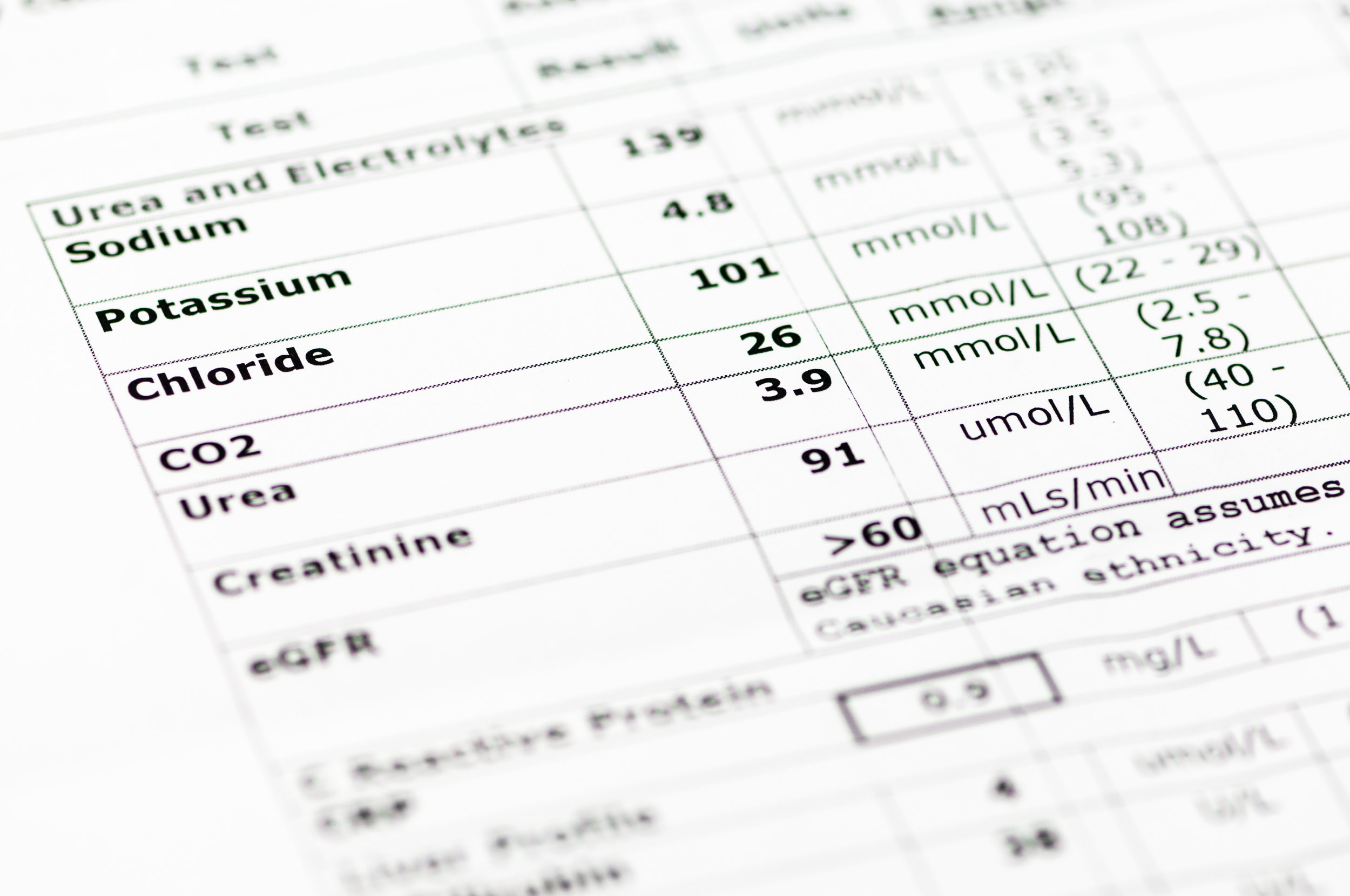

I theorized that the problem was either that the AI was based on information I had entered that no longer applied or that the pump itself was broken, but no one at the manufacturer knew enough to help me figure it out. My only option was to go back to basics, basics I hadn't needed to employ since my first pump in 2001. I started running fasting tests to figure out what my true insulin dosage should be.

And that's where I am now. If I got it right, I will try talking again with the manufacturer to see if they can answer my questions about why the AI doesn’t work when all the other parts do. I still hope I will get to use the AI eventually. It sure would make life easier. But for now, I will keep the two halves of my new device separate: one half proven tech upgrades (the CGM) and one half methods that have been around since the first injections (manual insulin calculation).

So please, try not to do what I did and assume that every new device will be the only solution to problems that have been effectively addressed for decades. Keep an open mind and see more than the easiest path. I wouldn't want anyone else to end up with the disappointment of a basket of broken eggs.